An anti-democratic mini-meme developed amongst some of my liberal friends in the build-up to the EU referendum. For some people, democracy is a virtue and governance structures that provide more direct democratic accountability are inherently superior to systems that are less responsive to the will of the majority.

Just hope the English people take the first step tomorrow in dismantling the undemocratic EU #VoteLeave #Brexit https://t.co/CWOKGTwWDK

— Patrick Henry (@patrick_d_henry) 22 June 2016

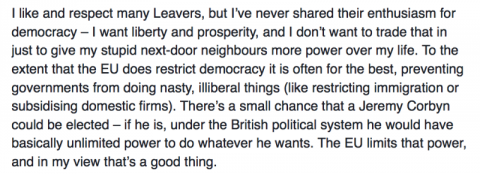

Prompted by such naive comparisons, some libertarians respond that the democratic limitations of the EU are a virtue.

A Remainer says the EU isn’t democratic – and that’s a feature, not a bug https://t.co/YuO97QPuUy

— Sam Bowman (@s8mb) June 23, 2016

Some of the criticisms of democracy are unarguable.

Why is the opinion of every person on every subject equally valuable, regardless of their understanding of the issues?

I've decided to vote Remain. Here I explain why: https://t.co/5EH4YhV3pL

— Sam Bowman (@s8mb) June 21, 2016

That's the problem I have with the we-must-take-back-control line. That "We" also includes @s8mb's neighbours. https://t.co/UHlue4YSqm

— Kristian Niemietz (@K_Niemietz) June 22, 2016

You do not have to resort to calling some electors stupid to make a compelling case that most people are rationally ignorant on policy issues. But every voter has an equal say. There may be little substance to the views of the majority that decides the government.

Indeed, public-choice economics teaches us that the programs of parties seeking democratic approval are unlikely to be based on altruism or economic efficiency. Policies will be designed to “buy votes” from enough interest groups to secure a majority.

In the worst case, this can become the “tyranny of the majority”. There must be some constraint on the ability of the majority to oppress minorities.

Regular changes of policy in response to swings in democratic opinion increase uncertainty and commercial risk, and thereby impose a drag on the economy. An ideal model where policy was rational, limited and changed rarely would be more efficient. Some people believe that the greater stability and prosperity enjoyed under “benevolent autocracies” may be a better compromise between economic and political freedom. At the libertarian extreme (e.g. Hoppe), dissatisfaction with the democratic impacts on economic freedom leads to a preference for monarchy over democracy.

Most liberals do not favour a reversion to absolute monarchy or autocracy. They want constraints on democracy. But is it any less of a fallacy to regard something that constrains democracy as inherently virtuous simply because it limits the power of the majority than to regard something as inherently virtuous simply because it is democratic? The nature of the constraint matters.

Sensible liberals will hopefully agree on the rule of law as the most important constraint, so long as that protection is not undermined by hyper-legislation. Representative (rather than direct) democracy separates the choice of the decision-makers from the decision-making itself. An undemocratic revision chamber provides further insulation from the will of the people, although not necessarily from the will of the political parties that put most of them there.

For some, these constraints are not enough. Representatives may be more informed than the average person, but they are still generalists voting on issues on which they are mostly not qualified. And they are answerable to the “great unwashed” and therefore vulnerable to pressures to side with an irrational majority view. What some long for is governance by people who are expert in their field and immune to public pressure. To this perspective, the European Commission can seem a step further towards this “ideal” and therefore, although not perfect, better than the traditional British model of democratic governance.

Thanks to the use of projections as “evidence”, the role and reliability of “experts” became an issue for the referendum. Many people, including some liberals, poured scorn on the Leave camp’s disdain for experts. Given the limitations of public knowledge on policy issues, it is natural to feel that the views of experts should be given more weight than public opinion. In the frequent moments when democratic pressures have produced unwise policy, I have felt the attraction of a meritocracy or technocracy.

But how do we organise that? Who picks the right experts? How do we make sure they have sufficient, accurate and current information to make their judgments? How do we tell if they got it wrong, and how do we replace them if they do?

These are the kinds of challenges posed by Hayek, who also explained the tendency of intellectuals to overlook these challenges: “intelligent people will tend to overvalue intelligence”. Even, apparently, some of those who generally agree with him...

It is not clear whether the EU or national governments rely more heavily and unwisely on experts. This has been the era of technocratic government.

The British Establishment has carped about the EU for decades. Their opposition to Brexit can be understood largely on the basis that the EU is a handy excuse when implementing expert-devised policies that might be a hard democratic sell. “The Directives are a compromise between 28 nations, and we have no choice but to implement them” they say, as they convert generic obligations into badly-conceived legislative minutiae.