Mark Wadsworth (whose blog is one we recommend in our blogroll) managed to get a long (by their standards) letter published in yesterday's FT, criticizing John Redwood's focus on reducing corporation tax, when in Mark's opinion greater emphasis should be placed on reducing VAT and National Insurance (NI). Well done for getting published, Mark. You are half right.

You are right that some taxes need reducing more urgently than corporation tax, and that NI is one of them. On the other hand, Redwood is nevertheless right that we need to cut corporation tax (if not as a priority above other cuts), and you are wrong about VAT as a priority.

I say this with some confidence, because I happened, the day before, to be browsing the latest version of Taxation trends in the European Union - Data for the EU Member States and Norway, from Eurostat, the EU's statistics office (yes, I am that sad). The figures in there do not support Mark's argument in its entirety.

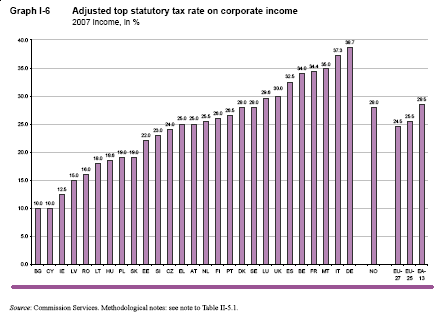

Corporation tax needs cutting because, although our biggest competitors have higher rates, we are not only in competition with them, but with the 20 other European countries that have lower rates than us. Not to mention the BRICS countries, and other developing nations. Your principal competitors change according to who is competing most aggressively. The best way to lose your competitive position is to focus complacently only on your old competitors.

Corporation tax needs cutting because, although our biggest competitors have higher rates, we are not only in competition with them, but with the 20 other European countries that have lower rates than us. Not to mention the BRICS countries, and other developing nations. Your principal competitors change according to who is competing most aggressively. The best way to lose your competitive position is to focus complacently only on your old competitors.

(Having said, that, one does need to be careful about what one means by "competitiveness", as Samuel Brittan, pointed out in yesterday's FT. But the conditions that influence where businesses choose to invest and to book more or less of their profits does seem a legitimate area for international tax competition.)

It also needs cutting because high rates of corporation tax distort investment decisions, as companies structure deals and decide their levels of borrowing and saving in order to minimize their tax bills rather than because of the fundamentals. And because experience in countries (particularly in Eastern Europe) in recent years suggests that high rates are at an inefficient point on the Laffer Curve, and that cutting rates to below our current level can increase (or at least, not significantly reduce) revenues.

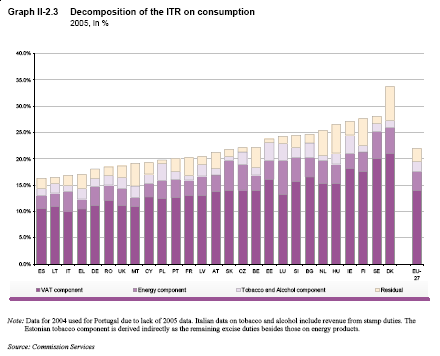

Although the comparisons for consumption taxes indicate that the UK's rates are already pretty competitive, it would be misleading for me to suggest that we are in competition over rates of VAT in the same way that we are in competition on corporate tax. Most of us do not have much option to go to another country to consume our goods. The costs of doing so are likely to be very much greater than the tax benefit. Nevertheless, it does raise doubts as to whether further reductions in VAT should be an urgent priority.

Although the comparisons for consumption taxes indicate that the UK's rates are already pretty competitive, it would be misleading for me to suggest that we are in competition over rates of VAT in the same way that we are in competition on corporate tax. Most of us do not have much option to go to another country to consume our goods. The costs of doing so are likely to be very much greater than the tax benefit. Nevertheless, it does raise doubts as to whether further reductions in VAT should be an urgent priority.

VAT does not have much impact on costs of production, thanks to the offsetting of VAT on purchases against VAT on sales. It is effectively a tax on final consumption. Apart from the case of one-to-one transactions involving personal services (e.g. paying in cash for your gardener or cleaner), it is relatively unavoidable. Nor is it so high (at 17.5% nominal, 11% implicit, i.e. taking into account lower rates and exemptions) that it will be deterring significant levels of economic activity, relative to other taxes whose rates are significantly higher. Consequently, a reduction in VAT is likely to have a near-proportionate impact on tax revenues - there is unlikely to be a significant Laffer-Curve benefit.

Mark argues that "VAT does not just increase the price paid by the consumer; it also reduces the net price received by the producer. Thus low-margin producers are forced out of business and output is reduced quite significantly." Well, yes, it will be a bit of both, though the combined effect will remain 17.5% (or whatever rate of VAT applies to the good). The balance between one and the other will depend on commercial decisions, which will be heavily influenced by price-elasticity of demand. If demand is inelastic, producers should be able to pass on most of the cost to consumers without dramatically affecting volume, and therefore profits. If demand is elastic, producers will have to choose between passing on the costs to consumers and accepting a lower level of demand, or absorbing the cost to maintain volume, but reducing margins/profits. Their balance of fixed vs variable costs will play a significant part in that decision.

The net effect, as Mark says, is that some marginal products are not brought to market, the volumes of some other products are reduced, and the prices of goods that are essential or at least strongly desired, are higher than would otherwise be the case. But this is not different in effect to other taxes. Corporation tax also affects either the level of profits or the price at which the company's goods must be sold in order to deliver the return on investment necessary to persuade people to invest (or retain their investment). At the margins, it will also cause businesses not to be setup or to divert their funds into more profitable activities, which reduces the range of products available and the volume of transactions, and increases the price of goods for which demand is inelastic. And income tax and NI increase the cost of producing goods with a significant labour input, causing fewer of those sorts of goods to be produced and increasing the cost to consumers of essential, high-labour goods. All taxes have this sort of effect - it is a question of striking a balance between their impact on the economy and the need to raise revenue. In that regard, 17.5% (or 11% on average) on consumption could be expected to have a less significant impact than 28% on profits or 40-50+% on employment.

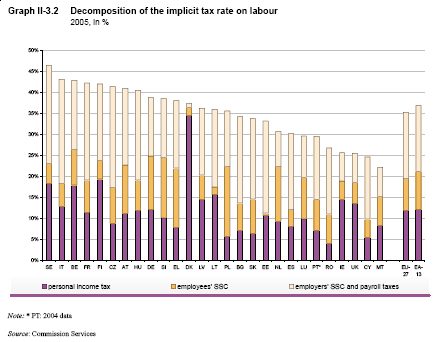

It is that latter figure that seems a particularly strong disincentive to something particularly desirable. NI, of course, is part of the tax on employment, and the most regressive part at that. I am in agreement with Mark on this, and yet the European figures once again do not appear to support us. The only countries in Europe with lower implicit (i.e. weighted average) tax rates on labour, including income tax and employer/employee social security contributions (SSCs, i.e. NI in the UK) are the tiddlers of Greek Cyprus and Malta. It seems that the UK government is taxing labour relatively lightly. Moreover, our SSCs are a relatively low proportion of the whole (less than half the average) compared to most of our neighbours, whereas our income-tax rates are higher than average, which might suggest that NI isn't even the place to start if one were reforming UK taxes on labour.

It is that latter figure that seems a particularly strong disincentive to something particularly desirable. NI, of course, is part of the tax on employment, and the most regressive part at that. I am in agreement with Mark on this, and yet the European figures once again do not appear to support us. The only countries in Europe with lower implicit (i.e. weighted average) tax rates on labour, including income tax and employer/employee social security contributions (SSCs, i.e. NI in the UK) are the tiddlers of Greek Cyprus and Malta. It seems that the UK government is taxing labour relatively lightly. Moreover, our SSCs are a relatively low proportion of the whole (less than half the average) compared to most of our neighbours, whereas our income-tax rates are higher than average, which might suggest that NI isn't even the place to start if one were reforming UK taxes on labour.

And yet, it is still true that our employment taxes are too high. Eurostat knows it too:

"Despite the presence of a number of low taxing countries, taxation on labour is, on average, much higher in the EU than in the main other industrialised economies. The effective tax rate on labour in the United States was estimated at just 23.9 % in 1999, compared with an EU-25 ITR of 36.3 % for that same year. Carey and Rabesona (2002) estimated a 24.9 % average effective tax rate on labour for the United States in 1999, i.e. 12 percentage points less than the estimate for the EU-15; the difference with Korea (13.9 %) was even more than 20 percentage points. Values for Japan (23.0 %), New Zealand (23.0 %), Australia (25.3 %), Canada (30.3 %), and Switzerland (31.1 %) were far below the EU-15 average, too. Martinez-Mongay (2000) found broadly similar differences between the EU and the United States and Japan. Indirectly this is confirmed by OECD data on the tax wedge."

And that's just the industrialised countries. The comparison with the developing nations will be even less favourable.

In this case, like corporation tax and unlike VAT, there is an element of international competition, as labour can move, if not as easily as capital. We see the effect in the inflow of Eastern Europeans to the UK at the moment (they could equally have gone to Sweden rather than Britain or Ireland, but the numbers were proportionately lower to the high-tax country that opened its doors) or the numbers of French already here, and the outflow of Brits to countries like Australia and the USA. The only country with higher taxes (and then not much, and not in terms of the proportion paid by the employee) to which there are major flows of Brits is Spain, and most of those are going there to retire.

The universal impact of taxes - of preventing some goods being produced, of reducing the volumes of other goods, and of pushing up the price of goods for which demand is least elastic - applies to taxes on employment as much as any other. But it manifests itself in specific and particularly harmful ways. The goods that are not being produced or are produced in lower numbers or are being made more expensive (without the producer benefitting) are jobs. The only way that high employment can be balanced with high taxes on employment is if people are prepared to accept a lower level of take-home pay. But as take-home pay has a significant impact on the sustainable level of demand in the economy, even that would not prevent high employment taxes from having a deleterious impact on the economy and people's wellbeing. And in practice in Europe, there is strong resistance to rebalancing levels of pay to take account of the cheaper labour and lower taxes that can be found elsewhere. The result is predictable and borne out by experience - high unemployment and low growth.

We may look smugly at the relative, official levels of unemployment and growth in Germany, France and the UK and believe that we are doing better than them. But while we undoubtedly have been doing better on average than those of our neighbours who have been slowly strangling themselves for the past decade or more, we are not so much better as the official figures might suggest. Our (un)employment figures are massaged by moving an incredible number on to disability benefit, and our employment figures are entirely dependent on the vast number of additional public-sector jobs (for which demand is unaffected by employment taxes because their "customers" - taxpayers - have no option until election-time but to pay the extra) that have been created since 1999. Worse still are our effective, marginal rates of tax (taking account of means-tested withdrawal of benefits), which provide a strong disincentive for those on benefits to seek work, unless they can jump straight into a high-paying job. We may only be mutilating rather than strangling our economy, and hiding our self-inflicted wounds better than our competitors, but it does not diminish the long-term impact, which is that competitors from outside Europe are catching us up or leaving us behind.

The first priority is clear, and I don't think would be in dispute between Mark, John Redwood and myself (though it would appear that Redwood's party, like the others, would dispute this). We must reduce the size and cost of government as much as possible, so that we are able to reduce the burden of taxation in general. But it will not be possible to reduce taxation to a level which has little impact. Priorities have to be chosen with regard to where the burden of the state should fall. As that burden is effectively a disincentive, it is, in significant part, a question of what one is least reluctant to disincentivize: jobs, profits or consumption (to limit ourselves to the three options considered by Mark). Though it is not ideal to discourage any of these, it seems to me that the least harmful of the three to deter is consumption, then profits, with employment being the least desirable thing to penalize. As things stand, the priorities are in exactly the reverse order. Redwood would rebalance it in favour of profits. Mark would rebalance it in favour of employment and consumption. I would rebalance it in favour of employment and, to a lesser extent, profits.

It seems that Mark and I agree on one other thing, though - perhaps more important than the levels of taxation, to complement the emphasis on reducing the level of tax on employment. Nominal rates are all very well and a worthy target for reduction, but what really matters are effective and marginal rates. This brings into play other factors, such as personal allowances and benefits. In comments on Mark's post, Vindico (a fellow individualist whose blog is now added to our blogroll) suggested that a flat tax be combined with a Basic Income (BI) to achieve a more efficient balance of effective and marginal rates of taxation. Mark agreed enthusiastically, and so do I.

I have been trying to promote BI as an efficient, liberal, compassionate alternative to welfare, and not necessarily a left-wing policy as many seem to assume, for some time. All reforms of the tax system, fiddling with the calculations for means-testing benefits, and sounding tough about forcing people back to work, will have little effect on the draconian levels of effective, marginal rates of taxation on low-earners that keep many of them out of work. Only a Basic Income can solve this. It is a sine qua non of genuine tax and benefit reform. If UKIP were to make it part of their programme, as Mark says they are considering, they would gain at least one more supporter.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 47.5 KB |

Comments

Tax reduction

Wow!

My initial observation is that you are still looking at VAT as a 'consumption tax'. It is not. I guess we are agreed whatever the legal incidence of a tax, there is not much you can do about the economic incidence. In fact, it is a turnover tax - which is what I tried to explain in my FT letter (some of which can be passed on via higher prices depending on supply and demand elasticities etc).

Next, what is the difference between production and consumption? In a largely service economy, it is a meaningless distinction. If you have your hair cut or attend a concert or whatever, somebody is producing and somebody is consuming.

Yes, there are Bad Things that the government wants to deter by slapping a tax on them (smoking, drinking, petrol, diesel, gambling - all of which are inelastic supply, so rakes in money without having much effect on amount consumed). But what is the difference between deterring consumption and deterring production.

Same thing, surely?

-------------------------------------------

As to corporation tax, you can't just compare rates with other countries, it's a lot more complicated than that.

More importantly, 80% of our economy is domestic. Worry about the domestic economy before you worry about inward and outward investment. Do you think that Tesco are going to shut down all their supermarkets and relocate to Ireland to take advantage of 12.5% corp tax rate? Nope.

Having a corp tax rate that is significantly lower than income tax rate leads to all sorts of distortions and tax scams (I should know, I am a chartered tax advisor) and discourages employment even more.

Think about it. For a basic rate employee of UK plc to get £67 after tax/NI (£100 less £22 less £11), the employer has to pay out £79 after tax (£100 plus £12.80 Employer's NI less 30% corporation tax relief). So the true 'wedge' is 15%. A worker has to be at least 15% more efficient that a machine to stand a chance of getting a job (if I can put it as crudely as that). (I often refer to 'Employer's NI' as being a bad tax, what I really mean is this 15% 'wedge', but it's roughly the same thing conceptually or mathematically.)

If the reverse were true, and corporation tax were 50% and basic rate tax plus NI only 30%, then businesses would employe people even where strictly speaking they should be using machines. Just as bad, but in other direction.

So the ideal (in terms of not distorting things) must be for corp tax and income tax to be the same rate (with no higher rate tax, or National Insurance on top).

----------------------------------

Imagine a self-employed hairdresser over the VAT threshold, what is his marginal rate of tax? If he does one extra haircut for £10, he has to hand over £1.49 in VAT, and £8.51 is his gross profit, on which he pays 41% tax/Class 4, so for doing that one extra haircut for which he charges £10, he is £5.02 better off after VAT and income tax/Class 4 NI.

In other words, VAT leads to a marginal rate of at least 49.8%. Why does it make the slightest difference to the hairdresser thay £1.49 of what he hands over is described by politicians and academics as a 'consumption tax' and £3.49 of what he hands over is described as 'income tax'? Clue - it doesn;t make hte slightest difference.

If the hairdrseer has to pay an employee £5 to do that haircut, the Treasury ends up with £4.96, the employer keeps £1.69 and the employee keeps £3.35.

So VAT is not insignificant. The fact that it is a lower nominal rate (17.5%) than corp tax (30%) is irrelevant - do not forget that VAT raises about £80bn, corp tax £50 bn and Employer's NI also £40 bn.

Tax reduction priorities

Bruno, do you have an email address? I will send you my plain English 5 page crash course in the impact of business tax. I sent this to John Redwood received a very nice reply.

Contact

I'd be very interested. To avoid me putting my address up where it can be harvested, could you use http://www.pickinglosers.com/user/2/contact in the first instance, and once I've got your address, we should be able to communicate in private.

As another thought, if you think this might be useful to a broader audience, we can stick it on here as an attachment to this thread.

Tim Worstall on corporation tax

Mark, I'm going to reply in detail, but in the meantime, there's some useful stuff on corporation tax at Tim Worstall's site. In my opinion, Tim tends to over-simplify for the sake of making his points punchy, and in this case, he has forgotten the possibly disproportionate contribution of smaller businesses to the total tax-take (and therefore what this tells us about tax compliance, competition and larger businesses), but this nevertheless illustrates the point about corporation-tax competition.

Priorities

Mark,

A lot of that is very enlightening, thanks.

1. VAT

I suppose it doesn't matter much what you call it, but if it is a turnover tax, it is one with very variable rates depending on the type of business. A business whose products include a low proportion of VAT-paying inputs (e.g. your hairdresser) experiences it as a relatively high turnover tax. If VAT-paying inputs amount only to 20% of the sales-price, the effective rate of VAT (at the standard rate) is 14.5%. On the other hand, a business whose products include a high proportion of VAT-paying inputs (e.g. many retailers) experiences it as a relatively low turnover tax. If VAT-paying inputs amount to 80% of the sales-price, the effective rate of VAT is 5.6%. So VAT disincentivises high-labour and high-margin products and services. But even at 14.5%, it is less of a disincentive to high-labour products than employment taxes at 40+%. You are right that to the hairdresser, it doesn't matter whether the tax is paid as VAT or NI, but that is as much an argument for reducing NI before VAT as vice versa. And not all businesses are hairdressers, or like hairdressers. Reducing NI will encourage employment in all businesses, whereas reducing VAT will encourage it more in some than others.

There is a difference between deterring consumption and production. Corporation tax and employment tax deter production of goods in this country (and/or payment of the tax on production in this country). VAT applies to goods consumed in the UK, whether produced here or abroad. I am not a protectionist - I don't want to deprive British consumers of the benefits of buying goods that were produced more cheaply abroad due to comparative advantage. But I do think it is going a bit far to put a greater burden on British production than its foreign competition, and thereby to drive it abroad. There is no doubt that this is happening, whether you look at the employment figures or the balance of trade and growth of production in countries like China.

You may counter that most of our economy is service not manufacturing, but (a) service is not just the stuff you receive on the high-street, in the office or at home - plenty of it can be driven abroad too, and (b) if you structure the tax system to reflect this balance, easing the burden on services at the expense of manufacturing, this becomes a self-reinforcing process. I am interested in a tax-system that is as efficient and fair as possible for everyone, not just for hairdressers.

2. Corporation tax

With regard to the merits of comparing our rates of corporation tax with other countries, do you remember saying in your letter to the FT that "at 30 per cent it is the lowest rate of the Group of Seven advanced industrialised countries"? What's sauce for the goose...

The problem with saying "If the reverse were true, and corporation tax were 50% and basic rate tax plus NI only 30%, then businesses would employe people even where strictly speaking they should be using machines" is that businesses have another option, which is to do neither. Likewise, investors have another option, which is not to risk their money and instead stick it in the bank or buy gold, or some other "safe" option. They may choose to buy property (under the illusion that prices won't fall), leading to an asset-price bubble. They may choose to invest overseas. These may all be marginal options, but an economy operates at the margins. I realise the above quote was intended as a bad example, but it would be equally true under your ideal balance.

Don't your calculations on the balance between employment and corporation tax treat employment as a zero-sum game - if you add an employee costing X, your profits are reduced by X (before tax)? As far as I can see, this assumption is necessary to assume corporation-tax relief on the full wage+tax cost of employment, but it is not true. No prudent businessman employs someone unless they believe that they will add at least as much value as they cost (in the long-run at least) and that profits will be retained, preferably enhanced, e.g. by increasing production or sales or improving efficiency, or, for those who are employed to meet regulatory requirements, reducing the costs of non-compliance.

I may have misunderstood how you get to 30% corporation-tax relief on the cost of wages plus employer's NI, but if not, the real comparison is between the employee's take-home of £67, and the £112.80 that the employer pays (ignoring other on-costs). That is a "wedge" of 41%, which provides a significant deterrent to employment, and it can be fixed only by reducing employment taxes (which we agree on as a priority). It is ineffective to try to compensate for this by balancing rates of corporation tax against rates of employment taxes.

3. The balance

When you compare the revenues from the various types of tax, you imply that the choice is between pro-rata reductions in revenues from each of them. In the case of VAT, you are probably right - a reduction of 20% in the rate of VAT is likely to reduce revenues from VAT by nearly 20%. There will be some Laffer-Curve benefit because there will be marginal reductions in avoidance and marginal improvements in economic performance, but it is a relatively hard tax to avoid and it is not likely that so many people who avoid it at 17.5% will choose to pay it at 14%. Let's say revenues fell 15%, that's a loss of £12bn to the Treasury. But experience in other countries with corporation tax suggests that reductions in the rate tend to have significant Laffer-Curve benefits, resulting in more not less revenue being received. We will probably not benefit to the same extent as Eastern European economies who moved from very high to very low (lower than we could probably afford) rates, but it is pessimistic to think that we would not see significant Laffer-Curve benefits from reduced avoidance (a propos of recent reports on levels of tax paid by many of our larger companies) and increased economic activity. A 20% cut in corporation tax (to around 22%) would be likely to cost the Treasury somewhere between £5bn and nothing. It's almost a "free hit". So it isn't so much a choice of which of the three to prioritize, as which of the other two (VAT or NI) to prioritize alongside corporation tax. As you can see, I believe that employment taxes are much the more important of the two, and that NI is the right place to start in reducing/simplifying employment taxes.

Incidentally, I would combine reductions of the various tax-rates with simplifications (no graduated levels, allowances or special rates of relief). Added to the BI rather than a byzantine welfare system, you would have a country in which people could make their choices according to their merits, and not according to the effect of tax and welfare impacts. Simplicity is perhaps the most important objective of all to improve our efficiency and quality-of-life.

Mark's crash-course

I've attached Mark's crash-course to this thread. You can find the link at the end of the original post. I haven't had a chance to have a good read yet, but will try to comment in due course.

Mark's paper

Mark,

That's a very useful reminder of the fundamental economics underlying tax decisions. People like to make things complicated nowadays, thinking it's clever, but the real intelligence is to understand the fundamentals.

I'll leave SVR alone - we've done it to death over at Tim's.

A small point that your paper addresses, which is absolutely right, is the effect of Minimum-Wage legislation on employment. This is another area where Basic Income would help, by making wage negotiations more equitable and reducing the penal levels of effective marginal taxation on low wages. The people who argue for a BI and a Minimum Wage really don't understand economics.

On the subject of the relative merits of the three taxes in question, as discussed in your paper, I'm not sure I have much to add to my previous comments.

Great Post

Great blog post Bruno and very interesting discussion on this subject. Certainly i think we can all agree that tax is too high at present and the Government is doing far too much - much more than it should be doing. Tax should parhaps peak at 30% of GDP as in my mind anything more is simply undermining individual freedom - my ideal would be down somewhere nearer 20% but that is perhaps a tad unrealistic.

The second issue is then where does the tax come from. Flattening and simplifying are of course good economically, although the shades of difference offered in a more complex system can help secure a competitive advantage. Certainly if desinging a tax system to raise the most revenue whils staying the most internationall tax competitive country then those businesses which are highly mobile and could relocate elsewhere would be charged lower rates of corporation tax and other taxes, while those which are immobile would be squeezed. Quite clearly a significant market distortion would be caused by Government and it is totally undesirable.

I think a basic income element which cannot be withdrawn, combined with a Negative Income Tax element which is withdrawn ad a low rate to 'top up' the BI according to need (e.g. disability for example, so that the total welfare sum is more tailored than a block BI) would be really neat. The maximum effective marginal tax rate should be 40% or less (ideally no mroe than 35% - perhaps a 25% IT rate and a 10% NIT withdrawal rate). If those are the parameters within which to work it should be relatively easy to design a good tax system.

The key though, is to cut the overall level of tax that needs to be raised. At present the tax system is complex but that means certain areas can be designed to be be internationally competitive. If you flatten the tax system it would simply show up all areas as uncompetitive.

ANyway I'll shutup. I'm starting to ramble. But keep up the thinking and thanks for blogroll add and hat tip.

Comparative advantage and the tax system

Vindico,

I agree with a lot of that - reducing the overall tax-level as a priority, the levels suggested as feasible and ambitious in the long-run, the market distortions from targeting taxes to maximize revenues, the desirability of BI and/or NIT, etc. Not rambling at all. I have just two comments:

1. Genuine comparative advantage does not come from playing with the tax system, but from allowing businesses to discover at which activities they are most effective, relative to international competition. Playing tunes with the tax system will actually reduce comparative advantage by encouraging investment in areas that are not genuinely the ones in which Britain has the greatest advantage. If they have a genuine comparative advantage, they will not need encouragement through tax distortions. If they need that encouragement, giving it to them is simply prolonging the malinvestment. And remember, if you reduce taxes on one sector to give them an advantage, you are going to have to put it on another, which will artificially disadvantage them. I don't think it's the job of the government to decide which sectors should prosper and which should struggle.

2. BI and NIT are really one and the same thing, structured in subtly different ways that have practical ramifications. Experiments with NIT highlighted the practical flaws - for instance, that a system based on the tax system relies heavily on annual assessments, which is too infrequent to be suitable as a welfare device.You can see BI, therefore, as a version of NIT adapted to deal with this flaw. Running both together would be fairly pointless. You can achieve exactly the same effect of BI + NIT with BI + variable rates of income tax, without the difficulties associated with NIT. From my perspective, if you have an adequate BI, the justification for variable rates of tax is reduced to the point where the benefits of a flat tax outweigh the benefits of the variable rate. For instance, one advantage of flat tax is that no account need be taken of domestic arrangements - if all earners in a household pay the same rate regardless, there is no question of some households (e.g. with one high-earner and a stay-at-home carer) being disadvantaged relative to others (e.g. with two medium-earning working parents). Once you have variable rates, whether NIT + income tax or variable rates of income tax, you either have to live with traditional families being disadvantaged, or the taxman has to get involved in people's domestic arrangements with transferrable allowances and the like, which is intrusive, bureaucratic and inefficient.

Simplicity is golden. Basic Income plus Flat Tax (BI+FT) serves the broad purposes of welfare perfectly adequately. Then, on top of that as you say, you need benefits to provide for genuine disability, but strictly in terms of medical need, not with reference to the person's ability to work. Then we can let our doctors stick to doctoring, and not have to act as social workers and benefits assessors as well.

Re: Comparative advantage

Bruno,

You do indeed make sme valid points. The tax system does distort market indicators and a neutral tax system would enable us to much better identify areas of real comparative advantage, not temporary advantage provided by a competitive tax regime in a particular area.

On your second point about the NIT and BI I would also add a further point. You say that BI and NIT are essentially the same and that a BI with a higher tax rate would achieve the same as an NIT. I would say that the problem there is that you would end up with a higer tax rate for all. My point was that a basic BI would be given to everyone, with some people's topped up based on their needs (e.g. disability). This second element would not be a grant-type benefit but would be withdrawn. Thus the flat tax rate can remain low, and only those receiving the extra beenfit would experience a temporary higher effective marginal tax rate (i.e. not all taxpayers have to put up with a higher marginal rate).

I of course take your point that it adds complexity to the system but I think it is necessary complexity, if not only on the basis of targetting welfare then also to be able to sell the concept politically. I have always favoured NIT because of its cost advantage comapred to a BI, but BI does not have the work disincentives of NIT. So a hybrid benefit with a fixed BI element and a variable/targetted NIT element might work better.

Providing the NIT element was kep simple - e.g. a single rate of withdrawal no matter hoe many targetted benefits you receive, at a low rate of, say, 10%, such that the maximum EMTR is no higher than 40% - i think it should add no great burden of administration.

But i do very much like the idea of scrapping the personal allowance and NI LEL and adopting a single low flat rate of tax, combined with a BI benefit. The advntage for employers in calculating the tax payemtn would be enormous. It would become a simple calculation as a % of their total wage bill. However a BI and a marginal tax rate which kicks in on the very first £1 of earnings would create a disincentive to work and so the rate would have to be very low.

BI and NIT

Vindico,

NIT is withdrawn anyway, by the nature of being a NIT. I'm not sure we're talking about the same thing. If the threshold is £10,000 and the NIT is -20%, then someone earning £7,500 receives £500 NIT, and someone earning £5,000 receives £1,000 NIT. Let's say the BI you proposed to combine with this were £4,000. You could achieve the same effect with a BI of £6,000 and an income tax of 20% upto a threshold of £10,000. Mathematically, it has the same effect, but administratively, the simpler system (without NIT) has many advantages.

I agree that disability benefits are required on top of a BI+FT system, but I don't see why they'd be income-related, rather than properly related to medical need. As soon as you make them income-related, you've increased the disincentive to work for those with disabilities, who already face greater employment obstacles than the majority. And you've dragged doctors back into making judgments based on the impact of the financial implications, rather than simply on the basis of medical need.

In my model, I have only one means-tested element, and that very reluctantly and at a low level, which is for single-adult households, on the purely political grounds that too many people would be too disadvantaged by the new system for it to be politically deliverable without inclusion of this factor. You could make a pretty good case for this also not to be means-tested. It's a choice between an increased disincentive to work for low-paid single-adult households (with the means-testing) or a broader incentive for all couples to live separately (without the means-testing). As BI is also substituting for state pensions, it is also a choice between giving additional support only to those widow(er)s with few personal savings, or to all widow(er)s. I felt that, given the generous provisions for spouses in most private pensions, the cost of making it universal, and the need for the state to stick its nose into the domestic arrangements of all households to whom it applies, the lesser of two evils was to withdraw the support gradually.

The costs of BI+FT are often misunderstood. It bothered me for quite a while. One instinctively thinks that a BI of £5,000 for 60 million people would cost £300 billion, which is far too expensive. But it's not like that. For everyone who is employed, BI could be administered simply as a deduction from the PAYE. In effect, it is an infitely-variable, but administratively-simple, progressive rate of tax (negative below a certain threshold). It is this fact that leads me to the conclusion that multiple rates of tax are an unnecessary complication to a BIFT system. And it also means that it is no more expensive in outlay and a lot cheaper in administration than a variable tax and welfare system that delivered a similar paid:net income profile.

This is hard to explain in abstract terms, and easier to demonstrate by example. I posted an illustration on another thread, but I'll copy it here. Here is a graph of how I believe effective and marginal tax-rates would work out against earned (not paid, an error in the labelling) income using illustrative figures of £4,500 BI, £2,000 means-tested single-supplement withdrawn at 7.5%, 43% flat-tax-rate:

This was done on the basis of an unchanged budget in other regards, as I believe it's important, for credibility, to be able to show that the proposal can stand on its own two feet, and not rely on savings from other areas that are difficult to predict. It assumes that the BI+FT replaces income tax, employee's NI, and most benefits and state pensions (except those, like some disability cover, provided on grounds of exceptional need). In practice, you'd be looking to make significant savings in other parts of government, which ought to go to reducing taxes on employment - both the income-tax rate and the employer's NI contribution. But even without such savings, this arrangement should be no more expensive than the current arrangements, only marginally impact people's net positions (some small losses and more small gains, rebalanced towards some groups, such as pensioners and families, who are penalized by the current system), would reduce the penalty on couples living together (married or otherwise) to the point where it should play little part in people's decisions on their domestic arrangements, and, most importantly, would significantly improve the incentives to work for those out of employment or on low pay, without significantly reducing the incentives to work for the better-off.

Incidentally, this is a year or two out of date now. The figures would need updating to make them comparable to current welfare provision, but the effect should not be significanly different, probably just a slightly higher BI.

Tax reduction priorities

Bruno, Vindico, I prefer agreeing with people to arguing.

----------------

On BI/CI we seem to be agreed apart from details, so there'd be more people looking for work.

----------------

Next, shall we agree that Employer's NI could be replaced with a fiscally neutral flat rate of (say) 7% on all salaries? Phasing this out over 7 years would reduce tax revenues by £5 bn per annum on a static basis, but of course net profits would go up, so corporation tax receipts would rise by £2bn, and employment would increase (remember that there are more people looking for work, from above) so income tax receipts would rise as well (or welfare payments would fall - same thing really) and so on, the dynamic reduction in tax revenues year-on-year would be negligible.

-----------------

Next, you accept (I hope) that for a VAT registered hairdresser, solicitor, chiropracter, car repair workshop etc, VAT functions as an additional income tax of at least 15% of turnover. If the car repair shop has a high non-VAT-able cost base, say rent and salary bill of £82.50 for every £117.50 of gross income, then the VAT would be 50% of gross profits, it would dwarf the owner's income tax bill. And VAT can drive a business into losses (unlike corporation tax - except in very unusual circumstances).

Your example of a low-margin retailer not having to pay much VAT over to HMRC is spurious. Let's pretend that business-to-business supplies were simply exempt. It then must be obvious to the retailer that it is a turnover tax of 15%. When you buy a fridge or something, you don't think "Great it was only £170! Pity I had to pay £30 VAT on top!", the fridge costs £200 and that is that.

So I am sticking to my theory that VAT should be phased out next. (I am not sure why this would be a burden on domestic manufacturers? Anyway, I am not going into international tax here, let's keep it simple). Of course there will be dynamic effects, that is the whole point!

If we reduce VAT from 17.5% to 15%, then on a static basis, receipts will fall by £10 bn. But businesses will become viable that would not be viable under the higher rate, so there'll be more business and more employment. And existing businesses will have higher net profits (they keep more of their turnover), so they'll pay more corporation tax, and so on. I have no idea what the dynamic fall in revenues would be, shall we say half of £10 bn, or £5 bn? This government wastes at least £50 bn per annum on the quangocracy, surely there's wiggle room for a cumulative £5bn tax cut each year, until VAT is phased out? (of course we'd have to leave the EU to do this!)

And don't forget that voters would like the idea of the price of goods going down! I think this is easily sell-able, politically.

----------------

I still think that corporation tax is the least of our worries (yes it could be simplified massively). Businesses set up factories in India or China because the labour is dirt cheap, and despite the fact that their corporation tax rates are slightly higher than ours. Like I keep saying, Tesco is not going to relocate all its stores to Ireland just to pay less corporation tax?

If anything, the next step should be to harmonise flat-rate income tax and corporation tax rates at 30%. This will iron out a lot of distortions. besides it is totally artificial to distinguish between "business" and "households" it is all the same thing, really.

----------------

Then of course finally we start reducing the flat rate income/corporation tax!