The Government and the opposition parties believe that climate-change and energy policy should revolve around identifying the technical solutions and their potential, calculating what each of them needs to encourage their deployment, and implementing mechanisms that provide just the "right" level of support for those solutions. They do not believe that, to whatever extent Anthropogenic Global Warming is a reality, emissions of greenhouse gases are an externality whose impact (and therefore social cost) is the same however and wherever they are emitted, and that the most efficient way to encourage less to be emitted is to apply that social cost to those emissions regardless of provenance.

Our politicos' assumptions of omniscience and omipotence tend to be undermined by reality. When it comes down to the reality of providing just the "right" level of support, they are amazed to learn (if they ever do) how many variables have to be taken into account, and how often it turns out that the information they were working on was wrong or has changed. Policy-making becomes a process of arbitrarily picking those variables that you will take into account (and about which you hope it is safe to generalize) and those variables that you will ignore and expect those who are disadvantaged just to suck it up, and then regularly changing them in ways that are unpredictable to investors. Such policies thereby achieve the brilliant combination of being altogether too changeable and complex (by taking account of too many variables) and yet partial and insufficiently reflective of the real-world (by ignoring so many inconveniences).

The recent banding of the Renewables Obligation (RO) was one such case, piling further complexity, irrationality and partiality onto many existing layers of partiality, irrationality and complexity. Now we have another case looming. A banded RO might be complex, irrational and partial, but it wasn't complex, partial and irrational enough for the politicians and civil servants. Some variables, particularly scale, weren't sufficiently covered. So they are bringing in a micro-generation Feed-in Tariff (micro-gen FiT), to support similar (though not identical) technologies to the RO, supposedly at a smaller scale, though the upper size threshold for the micro-gen FiT encompasses a large number of the projects currently included in the RO. They are also introducing, at more leisurely pace, a Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI), which will probably work in a similar way to the micro-gen FiT, but in the heat rather than electricity sector, and without (probably) the upper size limit.

The micro-gen FiT will provide a value beyond the ordinary electricity price, for each unit of electricity produced by an eligible micro-generation installation. It will be tailored supposedly to provide the "right" level of support for each technology. But that isn't specific enough, because the economics of a 5 kW micro-gen unit are very different to the economics of a 5 MW "micro-gen" unit (the upper threshold for eligibility, thanks to some strange definition of "micro" for public-choice and rent-seeking reasons) of the same technology. So the Government declared their intention to "band" the micro-gen FiT (and the RHI) not just by technology, but by scale too (and they were also considering banding by type of consumer, but hopefully have abandoned that option).

We know what the effect of banding by scale is. People make all sorts of irrational decisions about the type and size of plant, in order to achieve the maximum level of support under the bands. So, with the proviso that the whole approach is wrong but recognizing that something rubbish was inevitable and trying to minimize the damage, I came up with a suggestion for how they could achieve the same benefits that they wanted to achieve with banding without the harmful effects of banding. The suggestion was to "front-load" the mechanism, so projects would get a higher price for their first X MWh, and then a lower price thereafter. Large projects would get through X in a couple of months and would have to rely on the lower price for most of their lifespan, making the mechanism fairly similar to an unbureaucratic grant for them. Small projects would take years to get through X, and would therefore receive a higher level of support for a longer part of their lifespan. Medium-sized projects would fall in between, in terms of the effect of the front-loading. There were many advantages to this approach, but most importantly, there was no size threshold, so there was no disincentive to install simply the most appropriately-sized unit and technology for the circumstances.

To its credit, the industry broadly adopted and supported this idea, and extended it from the RHI (for which I had suggested it) to the micro-gen FiT. To rather less credit, but typically for a committee camel, the industry decided that they could improve the concept by making it more complicated, which was the form in which it was promoted to the government. Still, their bastardized version was a lot better than the Government's idea of banding by scale. Amazingly, for anyone with any experience of "consultation" in recent years, there were even some signs that the Government was giving the concept some serious thought.

We still wait for details of the RHI, but the Government has recently provided more detail on how it sees the micro-gen FiT being implemented. And guess what? Front-loading is out, and they are sticking with banding by scale.

We have to assume that this irrationality will apply in due course to the RHI as well. And I have some first-hand experience of the effect of that assumption.

As I have mentioned too often in recent posts, our company supplies wood pellets. I therefore have a stronger-than-average interest in installing a pellet-boiler for my home. As it happens, the cluster of three houses where I live make a particularly suitable opportunity for a micro-district-heating scheme powered by a shared pellet boiler.

We got quotes from a number of suppliers. They sized the project variously at between 60 and 80 kW. The prices unfortunately were all too high to be justifiable by the fuel-cost savings to be made, even though we were displacing the most expensive fossil fuel (LPG) and would have taken a longer-term view than most customers (given the commercial interest). The reasons why the capital costs are too high (and significantly higher than in other countries) is another story, also related to the effect of government intervention.

But sticking to the case in point, the main reason why the value did not justify the investment was the absence of any carbon value. Indeed, the low rate of VAT on domestic fossil fuels effectively creates a negative carbon cost, as those fossil fuels are cheaper than they would be if they were simply treated as any other product in the market. But after extraordinarily-prolonged cases of first myopia and then prevarication, something is on its way: the RHI. Doesn't that make the difference and justify the investment?

- When should I assume it will come in? The Government refused to drive it on the same timetable as the micro-gen FiT, which means that unlike the latter, the RHI will certainly not be introduced before the next election. The Government promise April 2011, but what value should one place on any policy promised by this Government to be introduced long after the next election?

- The Tories have said they would introduce something similar, so perhaps one would take a view on that (though I doubt it will be top of their legislative agenda). But what form should I assume the RHI will take? The Government couldn't even bring out some suggestions to accompany the panoply of consultations and policy-statements on low-carbon policy that they have released in the past couple of weeks. As I said, I am reduced to assuming that they will apply similar logic to the RHI as they apply to the micro-gen FiT. But what confidence should I place in that sort of assumption? They have shown an exceptional ability to reinvent the wheel at every turn so far.

- Perhaps I could take a view on the sort of mess that will emerge, knowing the similar predilections of Labour, Conservatives and civil servants for micro-managed complexity (whatever their denials). I am prepared to take an informed gamble that the RHI will be a FiT, that it will be banded by technology and scale, and that it will be introduced by 2012. But that is as far as I can go, and I probably know more about this than any other potential pellet-boiler customer. What will be the thresholds for the bands, and what will be the levels of support within each band? One can try to read the runes from what the Government has so far published, but in reality it's not much better than picking numbers at random. How does one invest on the strength of that?

For instance, what if (as is not unlikely, but not predictable) they make 50 kW a threshold between one band and another? And what if the level of support for boilers below that size is double the level of support for boilers above that size? How much of a plonker would I look if I now installed a 60 kW boiler? In those circumstances, I will obviously want a 50 kW boiler, and find ways to eke it out (larger buffer tank, or top-up from another heat-source). Or if I really want more than 50 kW, maybe I will divide the project and install two 35 kW boilers, attributing each nominally to a different property to be able to claim the higher rate on each, even though that is a dreadfully economically-inefficient solution compared to one 70 kW boiler. But what if I try to hedge my bets by going for one of these options, and then find that they have set the thresholds at 30 or 100 kW? Sizing sub-optimally is then money down the drain.

Clearly, I can't invest now, precisely because of the thing that is supposed to encourage this market. And whenever I do, I will not necessarily be installing the most suitable setup for the location, but the most suitable setup for the perverse incentives. A government proposal aiming to put right their failure over many years to treat heat equally to other forms of energy has, in practice, created the opposite effect for the foreseeable future. And all because they are so ill-educated in economics and deluded about the quality of their information and competence that they can't just do the simple and right thing: front-loading at the least, or better still scrap most of the existing and proposed mechanisms, replace them with a carbon tax, and let the market figure out where and how carbon can best be saved at less cost than the social cost of the emissions.

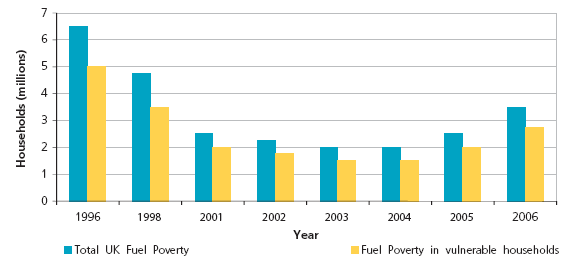

At 3.5 million, the number of homes in "fuel poverty" in 2006 was significantly higher than it was in 2000 (see graph from DEFRA's

At 3.5 million, the number of homes in "fuel poverty" in 2006 was significantly higher than it was in 2000 (see graph from DEFRA's