Hot air on green gas

Submitted by Bruno Prior on Wed, 25/02/2009 - 01:28For numerous reasons (some set out on other posts on this site), heat is a huge, vital, yet ignored sector of our energy systems. It is responsible for nearly half the carbon emissions from the energy sector. It is the reason we are so dependent on imported gas. Twice as much of our gas goes to producing heat as producing electricity. Europe could replace all its gas-fired electricity generation, and would still be as badly affected as this winter if there were further interruptions to one of its major gas supplies during a cold spell in winter.

Despite this, the British government has so far done almost nothing to reduce our carbon emissions and insecurity in the heat sector. Indeed, policy to date has been to keep gas heating so cheap that alternatives are not viable. As a result, we have grown steadily more dependent and inefficient (no point spending money or changing habits to conserve something so cheap).

The Government has finally proposed to consult on a possible support mechanism for green heat, but unlike the simultaneously announced policy to support largely-irrelevant micro-generation, it has refused to commit to a timetable to introduce the heat mechanism by April 2010. It will be 2011 at the earliest, they say.

The eagle-eyed may spot a slight problem with that: 2011 will be after the next election. In current circumstances, a promise by a Labour government to implement a mechanism in April 2011 should be more heavily discounted than a Ukrainian bond. It is unlikely that any new government, possibly apart from another Labour government with a big majority, will place support for green heat at the top of its legislative agenda. Most flavours of government (of the options likely to result from the next election) would not be likely to implement a green-heat mechanism in the form developed under this government. The upshot is that it is unlikely that any effective action on heat will be taken before 2012 at the earliest.

As it follows from this that Tory policy on green heat is likely to be more important, I went to see what they had to say. They have put so much effort into Energy and Climate Change that I had first to look up who their spokesman was. It is Greg Clark. (Readers may be equally surprised to learn that the LibDems' spokesman on the brief is now Simon Hughes. The Minister, Ed Miliband, has at least achieved a degree of visibility in presenting his brief to the public.)

Clark regards the DECC policy consultations on heat and energy efficiency as both "a knock-off copy" of Tory policy, and as "dithering" (which says what about Tory policy?). Instead of dithering, he wants the Government to "adopt the green policies outlined in our plan for a low carbon economy".

The only component of those plans, announced by Cameron in January, to deal with green heat are to "enable biogas, methane produced from farm and food wastes, to replace up to 50% of our residential gas heating". It looks like National Grid's bullshit has not been in vain, but has been swallowed whole by the Tories. In fact, the Tories have gone further, probably because they didn't read or understand the National Grid paper (perhaps because they only saw a pre-publication draft), which at least assumed that some of this gas would have to be ACT (advanced combustion technology) syngas, not just biogas.

Our company knows a bit about green heat and anaerobic digestion (AD, the process that produces biogas). One of our subsidiaries is the largest AD business in the country, producing more power from biogas than the rest combined (it's a big fish in a small pond). Another is a leading supplier of wood pellets for heating. I am the heat man, my brother is the AD man. What follows is my first stab to demonstrate how absurd this Tory "ambition" is. I will probably post again later with refinements based on more detailed and accurate figures from my brother, but the following figures are not unreasonable for illustrative purposes.

Don't take the following the wrong way. AD and green heat both have an important contribution to make (we wouldn't be leading the efforts to develop them if we didn't believe so). I am pointing out that they cannot contribute what the Tories think they can contribute, not arguing that a more achievable contribution from them would not be valuable. There is a strange perversion of logic in political circles, where something is only interesting if it can solve the whole or most of the problem on its own. Dismissing options that only make a partial contribution is like dismissing carrots because they only make a partial contribution to our diet. But it is an attitude regularly exhibited by politicians of all colours.

Anyway, with that said, let's proceed to the preliminary assessment of the Tory policy on biogas heating...

Residential gas consumption in the UK is around 350 TWh p.a. (more than total electricity consumption in all sectors). So the Tories' target is around 175 TWh of biogas. (1 TWh = 1,000 GWh = 1,000,000 MWh = 1,000,000,000 kWh or units.)

All the landfill gas produced and captured in the UK each year would provide around 1% of that target. Our sewage gas would provide another 0.2% or so. Just another 98.8% to find, then (and that's assuming these two sectors stop producing electricity).

If we need around 400 m3 of biogas for a MWh, 175 TWh for heating would need 70,000,000,000 m3 of biogas p.a. That's around 8,000,000 m3/hr.

A m3 of good putrescible waste @ 12.5% solids produces around 175 kWh. So to produce that much gas, we will need around 1,000,000,000 m3 p.a. of good putrescible waste.

Most waste isn't good putrescible waste of course, and one of the largest categories on which they hope to rely - agricultural slurry - produces little gas and needs a much higher ratio of waste and tank space to volume of gas produced. We could grow more, but we would need vast areas of land sacrificed to production of energy crops, which wasn't exactly a success recently even at smaller scale (proportionately) than required by the Tory policy. But for the sake of simple calculation, let's assume for a moment longer that this much waste of this quality could be found.

A m3 of digester tank can process around 13.5 m3 of waste @ 12.5% solids in a year. So we will need 74,000,000 m3 of digester tank to achieve their target. That's 9,260 Holsworthys (our AD plant in Devon - comfortably the largest plant in the UK, responsible for half of all UK biogas production outside the water industry); one for every 26 km2 and every 6,480 people.

And this assumes that no biogas is consumed or lost in the process of clean-up for grid-injection, and that no biogas is used for other purposes (e.g. electricity generation). Nor does it consider what we would do with that volume of digestate (nitrate vulnerable countries, anyone?).

The upshot is that we'd better grow and eat one hell of a lot of food if the Tories get in; an utterly impossible amount, in fact. Our current obesity epidemic has nothing on what they have in mind for us.

The reason they've gone for this technological "winner", of course, is that it seems painless (as all magic bullets do, until you have to explain why you missed the target), and it is promoted by a big company (National Grid), supported by a report from a big consultancy (Ernst & Young). Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

We have tried to engage with political parties on these sorts of subjects. But as we won't encourage their delusions, but will actually challenge them, they find that the best approach is to ignore us and cling to their delusions.

There is no point small companies, or others of independent mind, trying to engage directly with major political parties. They are not interested in the truth. They are blinded by money and power, and deaf to reason. It doesn't matter which flavour, they are all the same, other than in the choice of which interests to favour and lies to believe.

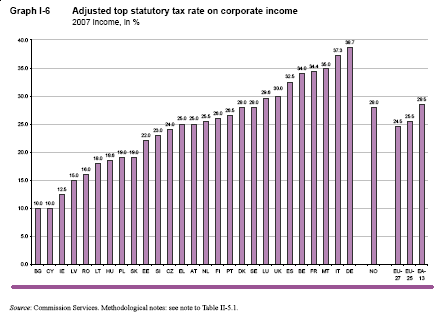

Corporation tax

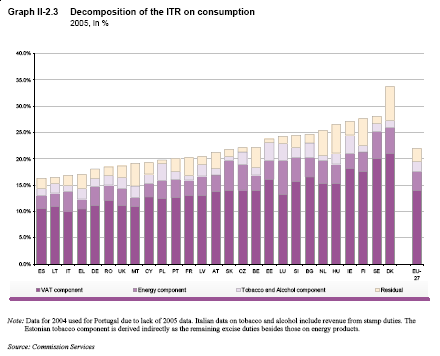

Corporation tax  Although the comparisons for consumption taxes indicate that the UK's rates are already pretty competitive, it would be misleading for me to suggest that we are in competition over rates of VAT in the same way that we are in competition on corporate tax. Most of us do not have much option to go to another country to consume our goods. The costs of doing so are likely to be very much greater than the tax benefit. Nevertheless, it does raise doubts as to whether further reductions in VAT should be an urgent priority.

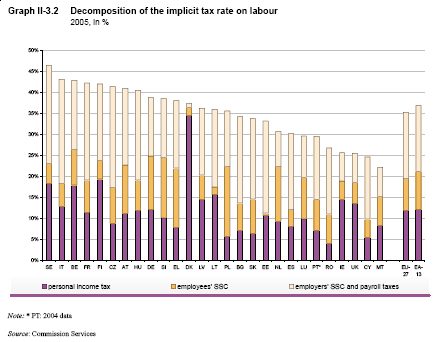

Although the comparisons for consumption taxes indicate that the UK's rates are already pretty competitive, it would be misleading for me to suggest that we are in competition over rates of VAT in the same way that we are in competition on corporate tax. Most of us do not have much option to go to another country to consume our goods. The costs of doing so are likely to be very much greater than the tax benefit. Nevertheless, it does raise doubts as to whether further reductions in VAT should be an urgent priority.  It is that latter figure that seems a particularly strong disincentive to something particularly desirable. NI, of course, is part of the tax on employment, and the most regressive part at that. I am in agreement with Mark on this, and yet the European figures once again do not appear to support us. The only countries in Europe with lower implicit (i.e. weighted average) tax rates on labour, including income tax and employer/employee social security contributions (SSCs, i.e. NI in the UK) are the tiddlers of Greek Cyprus and Malta. It seems that the UK government is taxing labour relatively lightly. Moreover, our SSCs are a relatively low proportion of the whole (less than half the average) compared to most of our neighbours, whereas our income-tax rates are higher than average, which might suggest that NI isn't even the place to start if one were reforming UK taxes on labour.

It is that latter figure that seems a particularly strong disincentive to something particularly desirable. NI, of course, is part of the tax on employment, and the most regressive part at that. I am in agreement with Mark on this, and yet the European figures once again do not appear to support us. The only countries in Europe with lower implicit (i.e. weighted average) tax rates on labour, including income tax and employer/employee social security contributions (SSCs, i.e. NI in the UK) are the tiddlers of Greek Cyprus and Malta. It seems that the UK government is taxing labour relatively lightly. Moreover, our SSCs are a relatively low proportion of the whole (less than half the average) compared to most of our neighbours, whereas our income-tax rates are higher than average, which might suggest that NI isn't even the place to start if one were reforming UK taxes on labour.